Lewisham 1957

When the driver of a steam train passed warning

signals and ploughed into the back of a stationary electric train,

the accident was serious enough - but when the collision took out the

supports of an overhead flyover, bringing 350 tons of steel bridge

crashing down, disaster turned to tragedy.

The combination of a dark winter evening, thick fog, signals missed, trains running out of proper order and the collapse of a heavy girder bridge led to the worst ever accident on the Southern Region of British Railways.

The two trains involved in the initial collision at Lewisham, in the south-east of London, were overcrowded, with nearly 1500 passengers in the 10 coaches of the electric train and 700 passengers in the main line steam train which ran into it. Casualties were inevitably high: 89 passengers and a train guard were killed and over 100 passengers were seriously injured.

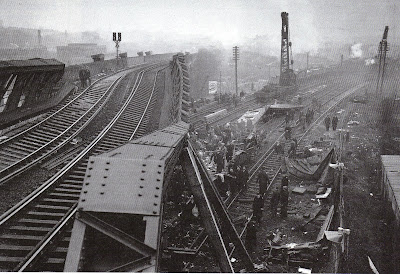

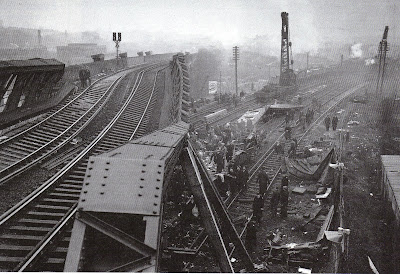

Rescuers work in the wreckage of the 4.56pm Cannon Street to Ramsgate train with the collapsed bridge girders above them. The second coach was totally crushed; this is the third coach (No 4378), the front part of which was destroyed

Rescuers work in the wreckage of the 4.56pm Cannon Street to Ramsgate train with the collapsed bridge girders above them. The second coach was totally crushed; this is the third coach (No 4378), the front part of which was destroyed.

The line was equipped with colour light signals controlled partly by track circuits which, although installed about 30 years earlier, were just as effective as the newer installations of the 1950s. So how did the collision happen?

Fog causes disruption

Wednesday 4 December 1957 was one of those days when fog had been hanging around the Thames basin in London. By dusk it had thickened up in places so that visibility was little more than 10 to 15 yards. Elsewhere, visibility was better at about 50 yards. The eastern section of the Southern Region, with its dense network of routes out of the main London termini, was badly affected and trains from Cannon Street and Charing Cross were running late and out of order.

The routes from these two termini combined in a complex track layout as they approached London Bridge, but by New Cross there were just four tracks - down and up local and down and up through - all equipped with colour light signals. At St Johns, the next station, a branch diverged from the local lines towards Lewisham Junction, while the local and through lines curved sharply to the right under a massive girder overbridge carrying the railway from Nunhead to Lewisham.

At about 6pm several trains were running on the down through line between London Bridge, New Cross, St Johns and beyond. The 5.05pm Cannon Street to Hastings train, steam hauled by a Schools class 4-4-0, had left Cannon Street 38 minutes late; it passed through St Johns at 6pm.

The train had lost more time during its journey as the driver, cautious after passing successive yellow signals, searched for signals in the fog. Even though colour light signals with their powerful electric lights can penetrate fog, in places the fog was so dense that night that the beams of light could barely be seen more than 20 yards away. The fireman of the 5.05 train said afterwards that some could not be seen even at that distance.

The driver of the 4-4-0 was seated on the left-hand side of the engine. Even though the boiler of the Schools class locomotive was not as large as those of other engines - notably the Battle of Britain class which was involved in the accident -his view of signals on the right-hand side of the track was partially obscured. As the train continued running slowly on towards Hither Green he asked his fireman on the right-hand side of the engine to look out for the signals through the fog.

Three minutes behind the steam train was the 5.16pm Cannon Street to Orpington electric train. With the driver right at the front and no massive boiler to obscure his vision, the driver had a better view of the signals both on the right and left. Even so, some signals were still difficult to pick out in the fog until they were very close. The train was travelling slowly, running past successive yellow signals as it was following the Hastings train ahead.

A few minutes behind was the 5.25pm Charing Cross to Hastings train, formed of a diesel-electric unit, with the driver right at the front like the electric train ahead. It had passed green signals until North Kent East Junction on the London side of New Cross, but then slowed as its driver saw yellow signals through New Cross and St Johns until it was stopped by a red signal at Parks Bridge. This was the setting for the drama which followed.

Diagram of the track in the immediate area of the accident

Signalling system

The signals at St Johns were controlled from the signalbox near the station, although a lever could not be pulled to clear a signal if a train was on the section of line beyond that signal. Many of the signals not controlling junctions were automatic and not worked by levers. The next signalbox ahead was Parks Bridge Junction which controlled the local and through trains and also a connection to the Mid Kent branch to Hayes.Trains were not offered and accepted as in manual block working but were simply described on the train describer. These clockwork instruments consisted of a clock face with a pointer towards up to 12 descriptions around the face and levers operated by the signalman to identify trains to the next signalbox down the line. There were two describers for each track, one to say what type of train was coming and one to say where it was going

Driver's view of signals

Normally signals were on the left of the line, but those between New Cross and St Johns were on the right. This was partly for space reasons and partly because when the signals were installed in the 1920s many of the steam engines on the line at that time had right-hand drive.

Later Southern steam engines had the driver's controls on the left, so that the right-hand signals had to be picked out before becoming obscured by the locomotive boiler. The extent to which the boiler restricted the driver's view depended on the type of locomotive. The Battle of Britain class Pacific involved in the collision at St Johns had a particularly wide, flat-sided casing, restricting the forward vision of the driver to a narrow spectacle glass.

In fog, if the driver could not see the signals on the right, he would either cross the cab to look out of the right-hand side or ask his fireman to look out for the signals for him.

It was doubtful whether the driver of the Ramsgate train realized he could not see the signals through the fog. He did not cross the cab, and only asked the fireman to look out when he saw the lights of St Johns station.

Events leading to disaster

The evening of 4 December 1957 was foggy and there were long delays to the crowded Southern Region rush-hour trains leaving the centre of London for Kent.

The 4.56pm Cannon Street to Ramsgate express, powered by a Battle of Britain class Pacific No 34066 Spitfire, was following the 5.18 Charing Cross to Hayes suburban electric train on the down fast line through St Johns. The St Johns signalbox controlled some of the busiest lines in the world, using continuous track circuiting to operate four-aspect colour light signals.

The local train responded to a red light and drew to a halt just beyond the overbridge carrying the Nunhead to Lewisham line over the main line. The driver of the following express, however, passed first a double yellow and then a single yellow warning signal, before finally applying the brakes as the train passed the red signal which was meant to protect the train in front. By then it was too late and the steam train ploughed into the back of the stationary local.

The accident left 90 people dead and 109 seriously injured, making it the third worst disaster in British railway history.

Battle of Britain class 4-6-2 No 34066 Spitfire which headed the Ramsgate train was repaired and returned to service. It continued to be based at Stewarts Lane depot and used on main line services to the Kent coast until electrification in 1961. After that it was used on surviving steam services on the main line out of Waterloo to the south west until it was withdrawn for scrap

Battle of Britain class 4-6-2 No 34066 Spitfire which headed the Ramsgate train was repaired and returned to service. It continued to be based at Stewarts Lane depot and used on main line services to the Kent coast until electrification in 1961. After that it was used on surviving steam services on the main line out of Waterloo to the south west until it was withdrawn for scrap Signalman's confusion

The signalman at Parks Bridge could not see the train in the fog. He did not know which train it was or where it was going. He thought from the train describer that it was an electric train for the Mid Kent line which branched off to the right at Parks Bridge.

The signalman could not clear the signals to the Mid Kent line because he already had a train coming on the up through line from Bromley North, and also another heading down the Mid Kent line from Lewisham station.

The diesel train driver telephoned the signalman from the signalpost to identify the train, but the signalman did not know from which signal the driver was speaking and thought the driver had given the number of the signal behind.

In the meantime the 5.18pm Charing Cross to Hayes, which had left Charing Cross 30 minutes late - three minutes behind the diesel -approached St Johns. This was the electric train that the signalman at Parks Bridge had mistaken the diesel for. Its driver had seen the yellow signals at St Johns and drew to a halt at the signal showing red behind the diesel train. The back of

the 5.18pm train was on the curve just beyond the Nunhead to Lewisham overbridge.

The 4.56pm steam train from Cannon Street to Ramsgate, hauled by Battle of Britain class 4-6-2 No 34066 Spitfire, had been badly delayed on the empty run from the sidings to Rotherhithe Road. It did not leave Cannon Street until 6.08pm but then had green signals as far as New Cross.

The next three signals, all on the right of the line, were at double yellow, single yellow and red, the last being at the country end of St Johns platform.

Driver W J Trew was on the left of the cab and his fireman, C D Hoare, had seen the green signal at New Cross and called across to tell Trew what aspect it was showing. Then Hoare carried on firing ready for the start of the climb to the North Downs, assuming that Trew would see the next two signals. Although these stood on the right of the track, they were on a left-hand curve and, in clear weather, would be seen easily by the driver in spite of the restrictions caused by the huge boiler. Neither driver nor fireman were expecting the fog to be so thick at this point. Whether Trew actually saw the next two signals telling him to

slow down was never established.

slow down was never established.

The next thing Trew saw was the station lights as the train ran into St Johns. Just as Trew called to Hoare to look out for the signal at the end of the platform, Hoare saw the glow of the signal light through the thick fog. It was red.

Hoare called the indication to Trew. The driver pulled down the brake handle to apply the brake, but it was too late. Just 138 yards beyond the red signal was the back of the 5.18pm Charing Cross to Hayes electric train, standing on the rising gradient with its brakes hard on.

The Ramsgate train was travelling at around 30mph, and the brake blocks had hardly begun to grip the wheels when the big Pacific locomotive ploughed into the rear driver's cab of the electric train. The force of the collision thrust the rear two coaches of the electric train forward and as these were both of a stronger BR standard pattern than those ahead of it, the ninth coach over-rode and completely destroyed the weaker body of the eighth coach.

The sudden stop by the engine caused the leading coach of the Ramsgate train to burst out to the left of the curve. This forced the tender up and out immediately beneath the flyover, where it hit and displaced one of the stanchions supporting the bridge girders above.

Within seconds of the initial collision 350 tons of steel bridge collapsed on to the leading coaches of the Ramsgate train. What remained of the first coach after the collision was crushed by the bridge. The whole of the second coach was flattened and the leading part of the third was wrecked. Of those killed it was thought that 37 were in the electric train, mostly in the eighth coach, and 49 were in the front three coaches of the steam train. Remarkably, the engine itself was not derailed and damage to it was not extensive.

A couple of minutes after the accident, the 5.22pm Holborn Viaduct to Dartford train approached the collapsed bridge. Fortunately it was moving slowly up to a red signal, and when the motorman saw the girders at an angle he was able to stop the train just in time.

Rescuers carefully remove a survivor on a stretcher from the seventh coach of the Charing Cross to Hayes suburban electric train.

Driver's shock

Driver Trew and Fireman Hoare survived the crash, but Trew was in a severe state of shock. What signals he saw - indeed if he saw either of the two caution signals - will never be known. At first he said that he had seen the yellow signals, then later he denied having seen the signals at all. Hoare had not looked for the signals since he thought Trew had seen them, and he had not realized that the fog would be so thick.

Trew was tried on a charge of manslaughter, but the jury could not agree a verdict. A second trial was ordered and he was found not guilty.

What went wrong?

The inspecting officer who chaired the inquiry into the collision placed the blame for it solely on the driver of the Ramsgate train. He concluded that the driver did not see the two signals at caution and the St Johns signal at red and did not apply the brake until his fireman called out that the signal was red.

The fireman's actions were not criticized since he probably did not realize how thick the fog was in the cutting between New Cross and St Johns.

The signalman at Parks Bridge mistakenly stopped the Hastings diesel train thinking it was bound for the Mid Kent line, but he was in no way responsible for the collision.

The scene from the wrecked bridge, looking south , on Friday 6 December after the engine of the Ramsgate train had been removed. A further disaster was averted on 4 December when the driver of a train approaching on the left-hand track over the bridge saw the leaning girders and stopped his train. It ran on to the bridge and was leaning but did not derail. All passengers were safely evacuated.

Action taken

Like many inquiries at this period into accidents caused by drivers passing signals at danger, the inspecting officer recommended the adoption of the warning type of automatic train control, today called the automatic warning system (AWS).

Although the SR management had their reservations about AWS, it was eventually installed. However, the system has since been blamed for several accidents where repetitive cancellation by drivers acknowledging caution signals has led to accidental cancellation at red signals. British Rail tested a new system -automatic train protection (ATP) -which had the potential to prevent a train from running into danger. But with privatisation looming, the political will wasn't there, and after privatisation the willingness of the private sector to fund installations of such equipment is non-existant as its not profitable.

An image from the "Dark Ages", a temporary speed restriction board that is illuminated by gas. No part of this installation was light to carry, it was all heavy and cumbersome. In this instance the speed restriction is a 30mph one, and applies to all traffic.

An image from the "Dark Ages", a temporary speed restriction board that is illuminated by gas. No part of this installation was light to carry, it was all heavy and cumbersome. In this instance the speed restriction is a 30mph one, and applies to all traffic. A slightly later type, relying upon batteries housed in the boxes at the base of the speed boards to provide power for illumination of the speed restriction sign during the hours of darkenss. On the fishtail and on the box holding the 30mph stencil, were light sensitive cells which switched the light source on and off as required. The stencil is of the earlier type used, white numerals on a blue background.

A slightly later type, relying upon batteries housed in the boxes at the base of the speed boards to provide power for illumination of the speed restriction sign during the hours of darkenss. On the fishtail and on the box holding the 30mph stencil, were light sensitive cells which switched the light source on and off as required. The stencil is of the earlier type used, white numerals on a blue background. This picture clearly shows a common modification to the bottom of the battery boxes, the addition of lengths of point rodding. This increased stability of the speed restriction signs when they were erected, but the knees, shins, and legs of many a railwayman will bear painful testimony as to how lethal those bits of point rodding could be.

This picture clearly shows a common modification to the bottom of the battery boxes, the addition of lengths of point rodding. This increased stability of the speed restriction signs when they were erected, but the knees, shins, and legs of many a railwayman will bear painful testimony as to how lethal those bits of point rodding could be. A distant warning board for a tempory speed restriction, this one in a point with restricted clearances, hence to use of a small fishtail. The stencils are of the later type, black numerals on a yellow background, and the speed restriction applies to any trains take the route ahead off to the left. 20mph for freight trains, 60mph for passenger trains.

A distant warning board for a tempory speed restriction, this one in a point with restricted clearances, hence to use of a small fishtail. The stencils are of the later type, black numerals on a yellow background, and the speed restriction applies to any trains take the route ahead off to the left. 20mph for freight trains, 60mph for passenger trains. Modern retroreflective speed restriction signs, these untilise a coating that will reflect any light that falls upon it with almost equal intensity. This is a reminder distant board for trains taking a route on the right, and is commonly used were station platforms and the like fall within the required distance between the site commencement board and the distant warning board.

Modern retroreflective speed restriction signs, these untilise a coating that will reflect any light that falls upon it with almost equal intensity. This is a reminder distant board for trains taking a route on the right, and is commonly used were station platforms and the like fall within the required distance between the site commencement board and the distant warning board. Retro-reflective.

Retro-reflective. Termination board at the end of a speed restriction, this one is one of the old battery power variety.

Termination board at the end of a speed restriction, this one is one of the old battery power variety. Commencement board, battery powered variety.

Commencement board, battery powered variety. Retro-reflective.

Retro-reflective. Retro-reflective.

Retro-reflective. Retro-reflective.

Retro-reflective.